The rapid emergence, and subsequent uptake of oncology real-world data (RWD) has ushered in a new age of cancer treatment — one where we are beginning to support real-time decision-making and empowering clinicians to be more efficient than ever before; however, in this new age we’ve found ourselves asking an age-old question: does the data we are using to help make these decisions truly reflect the patient in front of us? The question is more pressing when called to answer for the well-being of an entire population. Can the experiences of US patients tell a reliable story applicable to patients from other countries?

For health technology assessments (HTA), the question of data relevancy is at the forefront of decision-making. In these cases, decision makers are called to decide how well a given drug may perform in the real world, relative to the next best thing, and what a reasonable cost is for the added benefit for an entire population. So, ensuring that the population of interest is reflected in the data at hand is a crucial part of their process.

To illustrate the task, and it’s accompanying challenges, consider the fictional country of Transportugal, who has been presented with real-world evidence (RWE) from the US to support a label expansion for a product in their country. Though the US study was conducted with sufficient rigor, Transportugal’s subject matter expert is quick to point out some immediate differences between their country and the US, listed in Table 1, which cast doubts on the external validity of the study’s results.

Table 1: Differences in Cancer Care between the US and Transportugal*

|

United States |

Transportugal* |

|

Drug of interest is administered 35% in community, 65% in academic centers. |

Drug of interest is administered 100% in a community setting |

|

3 drugs available for treatment, with the drug of interest accounting for 30% of market share |

2 drugs available for treatment, with drug of interest accounting for 50% of market share |

|

Patients usually have limited access to supportive care |

Provides supportive care for all cancer patients |

*Transportugal is a fictional country used for exemplification

From the differences in Table 1, we can begin to understand why making decisions with evidence external from the population of interest is difficult. Don’t we expect differences in the site of administration to affect outcomes? And if the drug in question only accounts for 30% of the market share in the US, compared to the 50% in Transportugal, aren’t the cohorts fundamentally different?

In reality, the list of difficulties go on:

-

Do the guidelines and treatment pathways differ from country-to-country?

-

Are the same backbone therapies available to both groups of patients?

-

Are the frequency of visits and diagnostic assessments comparable?

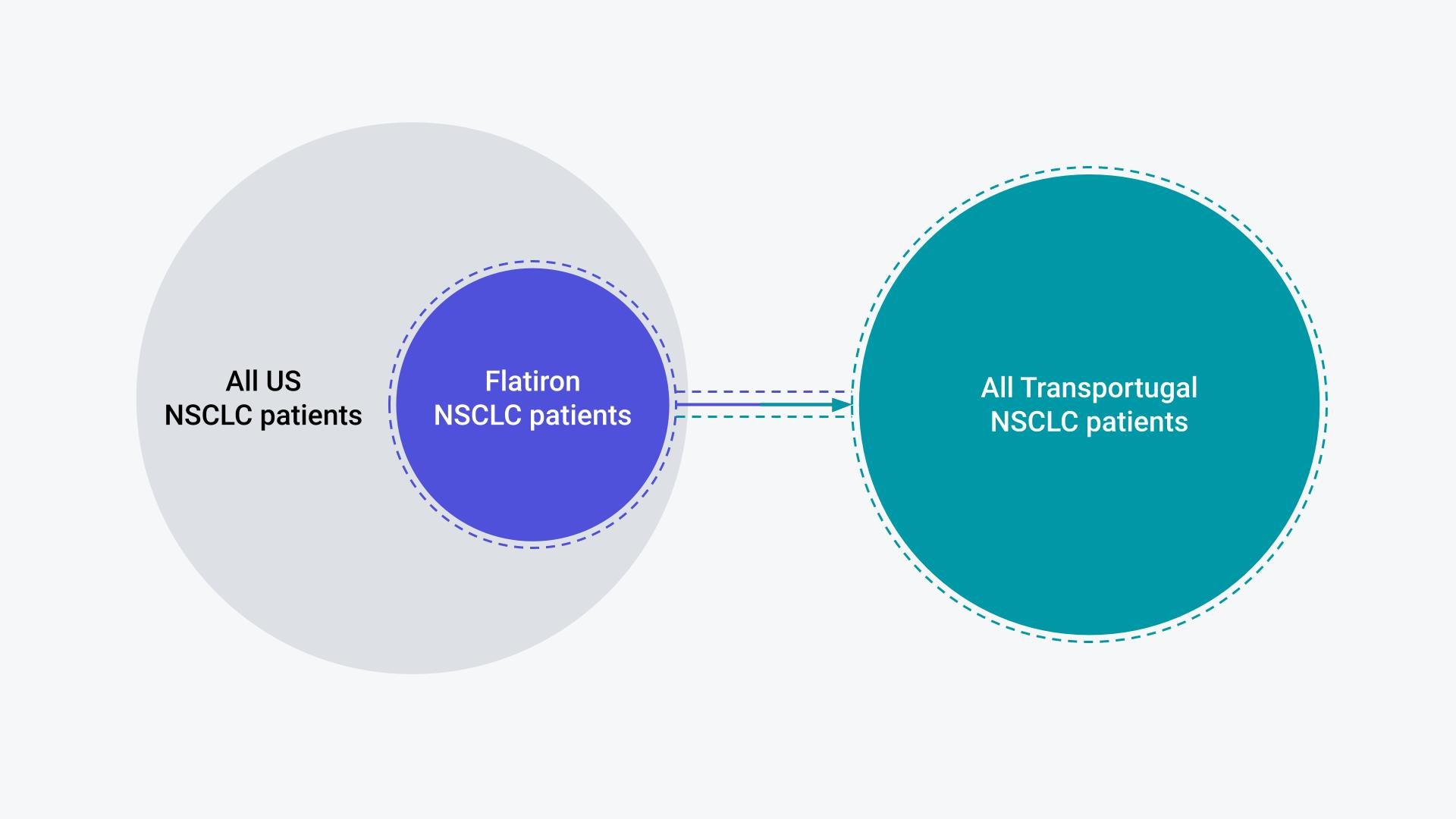

Questions, such as those provided above surrounding the relevance of US RWD to ex-US countries, are questions of uncertainty in the transportability (Figure 1) of inferences. Can the insights generated from the US transport to another country and allow for expedited decision-making and promote health equity both within the US and beyond?

Figure 1. Illustration of the Flatiron NSCLC patients as a sample of the broader US NSCLC population; Relevance of Flatiron RWE to the TRANSPORTUGAL NSCLC population requires assumption of transportability.

Though there is debate in the literature, we can likely never say for sure whether a given inference is transportable. We can never know with certainty whether the group of patients for which we intend to make a decision will have the same outcomes in another setting, such as Transportugal,* as they do in the US even with the same technologies1. A treatment provided to those with extensive caregiver support may realize more health gains than the same treatment provided to someone forced to provide for themselves; however, the data will view them equally. That is to say that in the data, those two patients are equal (eg, binary). In the data, the treatment was taken, or it was not, which makes transporting the true weighted effects difficult.

This is to say that with the results in-hand, one may find themselves pressed to retrofit them to a given target population. So then, our hope lies in the prespecification of our analysis with the goal of a representative population in mind. To help with this, we at Flatiron have created a list of considerations for the representativeness of US data for HTA decision-making (Table 2).

Using this framework, we can rethink how the study was pre-specified to prevent any undue anxieties thereafter. At a bare minimum, we can become more transparent about possible limitations to create an environment of trust, rather than the skepticism demonstrated by our fictional subject matter expert. For example, we probably could have identified differences in market share from the beginning of the analysis and knowing this may have changed how we constructed our cohort — to ensure those with access in transportugal are represented in the US EHR data. Or, we may have considered differences in site of administration and opted for a hierarchical model to handle these discrepancies.

Ultimately, there are a variety of ways that a target population may vary from that represented in any given dataset. The hope is that with the help of the considerations below, we can construct cohorts that are fit-for-purpose, identify populations similar to ex-US populations, and at the very least, be cognizant of the limitations that exist as we continue to push for a future where the full potential of RWD can be realized.

Download the framework: Considerations for the Representativeness of US EHR Data for HTA Use Cases

Notes: This table is intended to be a dynamic, living tool that will change over time. As Flatiron Health develops more learnings from experience with HTA use cases, and transportability nuances that arise, this tool will continue to be updated.

1 Hernán MA, VanderWeele TJ. Compound treatments and transportability of causal inference. Epidemiology. 2011;22(3):368-377