Original publication can be found here.

"This should be easier" said Karen Titchener , in 2018 for Huntsman at Home, about a program providing acute level "hospital at home" care along with palliative and hospice service for patients with cancer. At the time, she was the Director of Huntsman at Home, and was referring to the labor-intensive and lengthy process of reviewing patient charts to find a small percentage of patients that needed special attention. Who could benefit the most?

Data insights engineer Abigail Orlando listened carefully to Ms. Titchener and Dr. Kathi Mooney, the Director of Research and Evaluation for Huntsman at Home and co-lead of the Cancer Control and Population Sciences at the Huntsman Cancer Institute. Dr Mooney shared her excitement about the effectiveness of the program -- later publishing evidence of success of fewer and shorter hospitalizations -- which set the standard for high quality, at-home care for patients with cancer.

Dr Mooney and Ms. Titchener emphasized a challenging question for scaling this groundbreaking program: "How do we most efficiently identify patients who could benefit the most from this supplemental at-home care?"

Closing the Loop in the Learning Healthcare System

From use in protein folding to medical imaging, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) applications are everywhere in healthcare. But somehow, it's seldom incorporated into the workflow of caring for patients. One reason for low adoption is that clinicians are not sure the tool performs the way it is meant to; in addition, it seems that ML model accuracy metric AUC of >0.90 is the new p <0.05 for experiments in mice! The truth is that one metric will never be enough, especially when it comes to doing the right thing for patients.

Development and validation of ML-based tools for electronic health records (EHR) are key steps to initiate responsible applications in healthcare and should be followed by prospective evaluation in the real world. Recent findings suggest that just 2% of ML research is focused on the prospective use of ML.

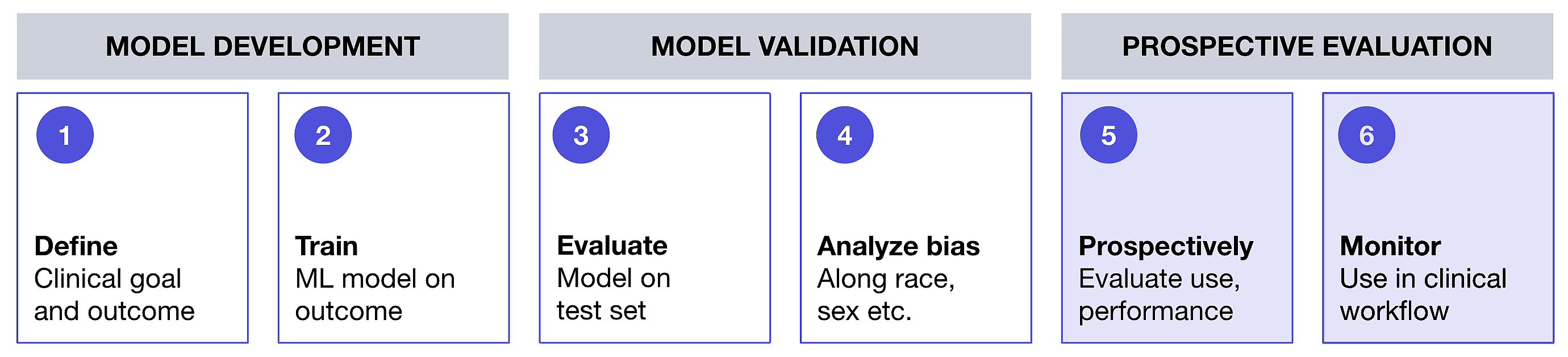

Our paper recently published in npj Digital Medicine builds a more solid framework to describe realistic stages from model conception to the incorporation into clinical workflows. We outline a process of converting a healthcare ML algorithm to a tool with defined clinical utility, by starting with an emphasis on the clinical objective and augmenting the traditional retrospective validation steps with prospective evaluation and monitoring. Importantly, we demonstrate the application with an example from Huntsman Cancer Institute.

Figure 1. High-level framework for deployment of machine learning model-based tool in a real world cancer clinic setting

Figure 1. High-level framework for deployment of machine learning model-based tool in a real world cancer clinic setting

Flatiron Health Machine Learning Team Partnered with Huntsman Cancer Institute

To help solve the roadblock Dr Mooney and Ms. Titchener mentioned above, the Huntsman Cancer Institute turned to Flatiron Health and its ML team to partner in translating the clinical challenge into a technical problem. Engineers, digital product and UX designers, oncologists and data scientists worked alongside clinicians and administrators to understand their workflows, objectives and pain points. Partnership between clinicians and engineers was essential to building a transparent and interpretable ML algorithm and defining how this could be embedded into existing clinical workflows to help make high-quality cancer care easier and more efficient.

To ensure that we made progress quickly and took advantage of the diverse perspectives in the room, our cross-functional team adopted an agile approach to product development. To start, the team put all their ideas, big and small, onto a large whiteboard. From there, we synthesized all our ideas into common themes and designed the first version of the ML model methods. Knowing that they were imperfect and certainly not the final version we would deploy, the engineers built the first prototype.

Getting to the Point (of Care)

Before deploying this ML tool at the point of care, the partnering teams identified key outcomes desired to ensure that the ML tool:

-

demonstrated value with retrospective data, a common standard,

-

achieved its goal when studied prospectively, and

-

could be embedded seamlessly into existing clinical workflows.

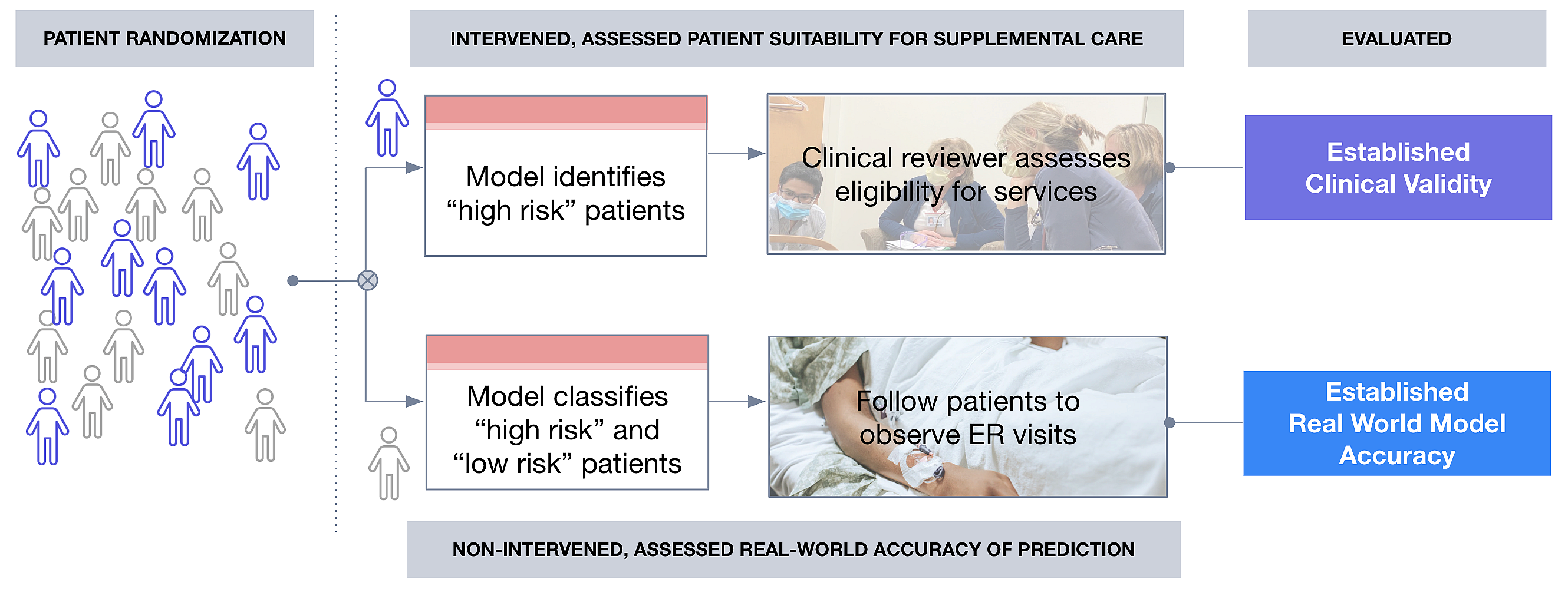

These discussions led to a joint prospective study in which patients with cancer actively followed at Huntsman Cancer Institute were randomized into two groups for which risk predictions from the ML model were conducted.

Group 1: patients with high-risk predictions from the ML model were surfaced for review of eligibility for the Huntsman at Home program and assessed following standard procedures (i.e. the only change was how patients were identified for review). This group helped assess the real world precision.

Group 2: patients followed the existing, unchanged care pathways for referral by care-providers to Huntsman at Home (i.e. no intervention in how patients were identified for review by the Huntsman-at-Home team).

For both groups, regardless of randomization, no component of the eligibility assessment or patient care was changed. This study design assessed the model's real world precision/recall relative to outcome prevalence. We also received qualitative feedback from end users that confirmed the ease of operationalizing the ML-based tool and incorporating it into workflows.

Figure 2. Conceptual diagram of randomized controlled prospective evaluation of ML tool

Figure 2. Conceptual diagram of randomized controlled prospective evaluation of ML tool

Having then assessed the ML tool performance and usability prospectively, we were ready for deployment.

The process of starting with a clinical objective and intervention in mind is foundational to a straightforward framework to ensure ML models are useful in practice and help deploy them at the points of care. These steps are summarized below.

Steps to develop and deploy a machine learning tool at the point of care

Strong multidisciplinary partnerships can produce positive outcomes in a repeatable way. A team of software engineers, data scientists, designers, clinicians, researchers, administrators, and managers developed a framework based on experience so that other institutions and patients could benefit from a systematic approach.

Here is our framework to develop, deploy, and evaluate an EHR ML-based clinical tool at the point of care to supports a clinician's independent assessment of patient risk:

-

Define healthcare system quality improvement goal met by predicting clinical event

-

Build or acquire ML-based clinical tool that predicts defined clinical event

-

Conduct retrospective evaluation of ML-based clinical tool

-

Conduct bias assessment of ML-based clinical tool

-

Conduct prospective evaluation of ML-based clinical tool

-

Embed and monitor ML-based clinical tool in clinical workflow

Overall, it is key to listen closely to the challenges described by frontline health workers and clinical administrators, remaining focused on the opportunity for technology tools to make meaningful gains in clinical workflow efficiency and patient outcomes.

Learn more about the ML framework and see an illustrative example from Huntsman Cancer Institute by reading the full paper in npj Digital Medicine.

More Resources

Ben-Israel D, Jacobs WB, Casha S, Lang S, Ryu WHA, de Lotbiniere-Bassett M, Cadotte DW. The impact of machine learning on patient care: A systematic review. Artif Intell Med. 2020 Mar;103:101785. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2019.101785. Epub 2019 Dec 31. PMID: 32143792.

Coombs L, Orlando A, Wang X, Shaw P, Rich A, Lakhtakia, Titchener K, Adamson B, Miksad R, Mooney K. A machine learning framework supporting prospective clinical decisions applied to risk prediction in oncology. npj Digit. Med. 5, 117 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-022-00660-3

Estevez M, Benedum CM, Jiang C, Cohen AB, Phadke S, Sarkar S, Bozkurt S. Considerations for the Use of Machine Learning Extracted Real-World Data to Support Evidence Generation: A Research-Centric Evaluation Framework. Cancers. 2022; 14(13):3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14133063

Mooney K, Titchener K, Haaland B, Coombs LA, O'Neil B, Nelson R, McPherson JP, Kirchhoff AC, Beck AC, Ward JH. Evaluation of Oncology Hospital at Home: Unplanned Health Care Utilization and Costs in the Huntsman at Home Real-World Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Aug 10;39(23):2586-2593. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03609. Epub 2021 May 17. PMID: 33999660; PMCID: PMC8478372.

Padula WV, Kreif N, Vanness DJ, Adamson B, Rueda JD, Felizzi F, Jonsson P, IJzerman MJ, Butte A, Crown W. Machine Learning Methods in Health Economics and Outcomes Research-The PALISADE Checklist: A Good Practices Report of an ISPOR Task Force. Value Health. 2022 Jul;25(7):1063-1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.03.022. PMID: 35779937.

Norgeot, B., Quer, G., Beaulieu-Jones, B.K. et al. Minimum information about clinical artificial intelligence modeling: the MI-CLAIM checklist. Nat Med 26, 1320–1324 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1041-